BY ELLEN CYNAR

From climate change to immigration; from the digital divide to gun safety; cities are grappling with how to address complex environmental and systemic issues that affect resident health. Along with physical or mental state, health is an expression of access, connectivity, and opportunity. Cities are increasingly held responsible for developing creative public health solutions that can respond to the unique needs of their communities; however, significant gaps in data and resources exist at the local level in support of these changes. The city of Providence is addressing this gap through partnership across unsuspecting disciplines, and by ensuring local public health efforts are both equitable and reflective of the community.

Providence is Rhode Island’s capital and largest city with approximately 179,000 residents, a sixth of the state’s population. Our residents are far more ethnically diverse than the state as a whole, with almost 42 percent of Providence residents identifying as Latino, compared to the 15 percent of Rhode Islanders. This is also reflected in the languages spoken within our community—nearly 21 percent of residents are non-English speaking, in comparison to only eight percent statewide. Providence’s role as the central hub for Rhode Island transportation, entertainment, education, health and social services only enriches the city’s vibrant cultural background.

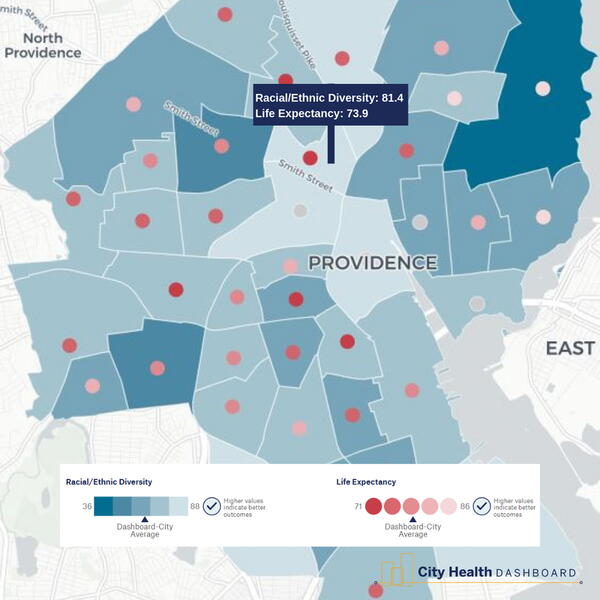

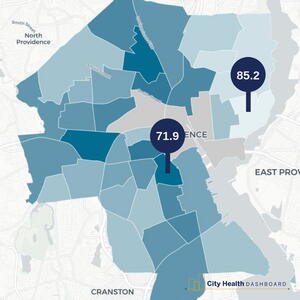

At the same time, racial and ethnic inequities faced by a large portion of Providence’s population contribute to disparities in health outcomes faced by many current residents. Some of the city's most diverse census tracts have life expectancies1 of 71.9 years—a full 10 years less than female life expectancy in Rhode Island—and six years shorter than all Rhode Island males. Economic disparities also negatively impact health outcomes in Providence; twice as many Providence residents live in poverty (26.9 percent) than in the state as a whole (13.4 percent).

Addressing health disparities in Providence’s diverse population requires a scalable approach at the community level. Without local data, however, cities like Providence are often forced to analyze or report health-related data at the county, state, or regional level, burying or diluting health inequities. When city-level data is available, it’s often irregularly collected, creating a static or inconsistently told narrative over time. The lack of consistency in reporting will ultimately fail to serve cities like Providence, where the social and environmental characteristics are far different than the counties or states in which they reside. Rhode Island’s consolidated health structure at the state level further exacerbates the issue, leaving gaps in local data surveillance. Therefore, overlooked or outdated data lead to policies and interventions that miss the individuals who need resources the most.

Supporting Providence’s current public health efforts is the Healthy Communities Office2 (HCO), the city’s lead agency for health policy and promotion initiatives. The HCO was created by executive order in 2012, following decades of dedicated substance abuse prevention work. As the scope of work expanded to better meet the needs of our community, the HCO became uniquely positioned as the coordinating body in the city of Providence for healthy living policies, activities, and systems improving public health outcomes for residents. This, coupled with cross-departmental problem-solving, has been a major source of Providence’s success in creating spaces and services that support health.

To address the lack of comprehensive, reliable city health data, Providence has partnered with the Department of Population Health at NYU School of Medicine3 to create a robust health data portal—the City Health Dashboard. Over the past three years, we have worked collaboratively with the NYU team and several other communities to identify indicators that are meaningful to cities and available consistently at the national level. The City Health Dashboard is now home to 37 indicators of health and its drivers for the 500 largest cities in the nation with a population above 66,000. When available, data is reported at the census tract level, enabling communities to develop solutions at a localized level.

Tools such as the City Health Dashboard are important first steps in understanding health at a city-level and provide a starting point for local government to implement health policy. This ability to examine demographic and neighborhood differences, and compare data across cities, aides in the identification of resources and best practices as a core function of city government. Whether it is the Department of Public Works; the Department of Arts, Culture, and Tourism; or Purchasing Office, the drivers of social and environmental health are often managed by departments that don’t have “health” in their title. Therefore, it’s critical that cities are prepared to use local health data to develop cross-departmental decision-making that supports equitable health outcomes for the residents they serve.

The HCO’s “health in all policies” framework engages a wide variety of community-based organizations; coordinates inter-departmental city resources; provides linkages to decision makers such as the mayor and city council; and facilitates community-driven plans as it relates to health equity. The HCO’s work has included the improvement of community parks and playgrounds; promotion of inter-modal transportation; funding to better engage children in nature-based learning; and program support for free meals in the city’s parks and recreation centers. Many of our documented successes use data to start a conversation and then develop interventions centered on the voice and experience of residents. Here are two:

Opioid Overdoses

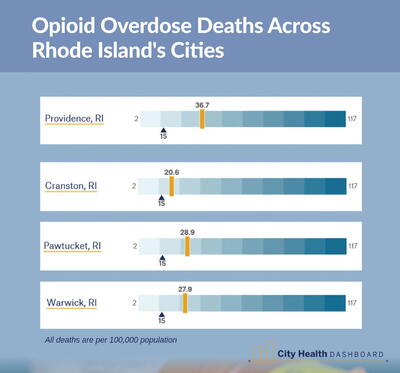

Like many cities across the country, the opioid overdose crisis has significantly impacted Providence, which experiences the highest rate of overdoses and overdose deaths in Rhode Island. 4 Serving as frontline responders is Providence EMS, which is integrated with the Providence Fire Department. Although the city has historically worked with state and local agencies to address the opioid epidemic, local leaders recognized that more needed to be done.

In 2017, the HCO partnered with Providence EMS to design a new methodology for identifying overdose incidents and analyzing overdose data. The HCO also partnered with graduate students from the University of Pennsylvania’s Master’s of Urban Spatial Analytics Practicum to develop a spatial risk model of opioid overdoses for the city. This new statistical methodology and modeling has identified high risk geographical areas in order to target interventions and outreach activities for overdose prevention.

In January 2018, the HCO and Providence EMS partnered with The Providence Center, the state’s largest and most comprehensive community-based behavioral health organization, to launch Providence Safe Stations (www.pvdsafestations.com). The purpose of Safe Stations is to address the overdose epidemic by providing quick, confidential access to supportive services. Available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, an individual can visit any of the city’s 12 fire stations, speak with the trained staff on duty, and immediately get connected to treatment support and services via peer recovery specialists. In the past year, over 125 individuals have accessed Providence Safe Stations and the program has served as a model for cities across Rhode Island and the country.

Youth Obesity Prevention

Obesity—and its associated racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities—disproportionately affects Providence residents, especially youth.5 Of local concern is the documented combination of sedentary activity and lack of access to healthy meals, when school is out during the summer months. To address the issue, obesity-prevention researchers have proposed several solutions including greater access to physical activity programming and healthy foods throughout summer months.

Providence has numerous built-in assets to support childhood obesity prevention, including its 100+ neighborhood parks and green spaces, which are within a ten-minute walk for all resident youth from any point within the city. There are also 12 recreation centers located throughout the city that serve as important neighborhood hubs.

Providence also administers the state’s largest free summer meals program for youth. Historically, these resources have been underutilized by residents. For example, in 2012 an estimated 11 percent of Providence youth participated in the summer meals program, despite the almost 90 percent eligibility for free or reduced school meals. In 2014, the HCO embarked on a multiyear needs assessment to identify barriers to participation in summer activities, which involved talking with youth and families in order to help identify points of engagement.

This needs assessment work resulted in the development of the Eat Play Learn PVD Initiative, a partnership between the mayor’s office, HCO, city departments, and dozens of community partners. The initiative has three goals: ensure access to healthy, fresh food options (“Eat”); encourage physical activity and creative engagement (“Play”); and increase yearlong learning and summer employment opportunities (“Learn”). The result is a coordinated approach to community engagement in summer activities, and resources that support youth health, including obesity prevention. Over the past four years, Providence has seen significant increases in summer meals consumption, parks use, and summer learning and recreation programming under the Eat Play Learn PVD Initiative. The continued success of this initiative is rooted in a combination of thoughtful analysis of local data, coordination across departments and community partners, and community-driven solutions to reach all Providence youth.

These initiatives are examples of how local government health policy, implemented using local data collection, supports Providence’s most vulnerable communities. Providence is not alone in the increasing responsibility cities are facing to provide opportunities for sustainable healthy living. Though the nuances of each city can add layers of complexity to what is representative of “health,” Providence is an example for what is possible through internal and community-wide collaboration. Data-informed decision-making and cross-sector collaboration is just the beginning of the process to making our city a more inclusive, thriving community.

ENDNOTES AND RESOURCES

1 https://www.cityhealthdashboard.com/ri/providence/metric-detail?metric=837

2 http://www.providenceri.gov/healthy

3 https://med.nyu.edu/pophealth/department-population-health

4 https://www.cityhealthdashboard.com/ri/providence/compare-cities?metric=26&comparisonCity=176

5 https://www.cityhealthdashboard.com/ri/providence/metric-detail?metric=29

ELLEN CYNAR, MS, MPH, is director, Healthy Communities Office, Providence, Rhode Island (ecynar@providenceri.gov).

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!