Home to the Palouse, Yakama, and Spokane Nations, the city of Palouse (population 1,015) is located in Whitman County in southeast Washington. Soon after the town’s establishment in 1874, a blacksmith and livery stable set up shop at 335 East Main. As petroleum-powered machines replaced human and animal agricultural labor, that gave way to a welding shop, and in 1955, a Conoco service station.

With five above-ground and four underground storage tanks, the Conoco was a significant operation covering one-third of an acre. In 1977, it sold to Palouse Producers, a regionally prominent supplier of agricultural fuel and supplies. And in 1985, Palouse Producers declared bankruptcy.

That bankruptcy was part of a larger trend. “The farm economy took a real hit in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s,” reflects former city attorney and orchardist Stephen Bishop. “I cut my teeth doing farm bankruptcies during that era.” As businesses closed and buildings became vacant, Palouse shed jobs and property values ticked downward. It was a vicious spiral that rendered the surrounding area unattractive for investment. Even two miles northeast of town, the appraisal on Doug Wilcox’s farm came back low. “The problem was that the average traveler coming to the farm…had to go through Main Street,” Wilcox explains. “Banks denied loans because you couldn’t not see the state of downtown.”

An environmental blow followed the economic one. Recounts Bishop: “[Palouse Producers] was already in bankruptcy court when people noticed, especially in high water, a sheen—an oil slick—going down the river.”

One Step Forward and Two Steps Back

To address the immediate threat of oil entering the Palouse River, Palouse Producers installed interceptor trenches, although these were not maintained for long due to its bankruptcy. The Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology) removed almost every regulated storage tank at the former Palouse Producers’ site in 1984 and 1985. The last known tank came out in 1992. And then the former Palouse Producers site, like so many other contaminated properties, sat. Around it, economic dislocation continued apace. Sure, people still needed to come downtown to collect mail, pick up groceries, or pay their taxes, but Main Street was a shadow of its former self.

For the old Palouse Producers site, there was no clear path forward. Under the federal 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Responsive, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, also known as the Superfund Law), anyone who owned a contaminated property could be held responsible for its entire cleanup. The risk was clear: no one was going to touch this site.

Then in 1996, the Palouse River added insult to injury with a 500-year flood event that impacted almost every building on Main Street. “It was a flood that no one could remember happening before,” says Bishop. “What was born out of that was a new awareness. People suddenly started to realize that downtown needed help,” he continues. In 2000, the local government embarked on a $2.5 million downtown revitalization project to repair and upgrade Main Street’s utilities and sidewalks, with funding cobbled together through state grants. It became the impetus for other post-flood improvements, like Doug Wilcox’s decision to buy and donate a dilapidated theater to the city, which demolished the building in 2001 and eventually built a new community center on the site.

While downtown’s recovery lurched forward, the Palouse Producers’ site stood out as a symbol of what was holding the city back. It was still tied up in bankruptcy court. It stood in the middle of Main Street, one block from the grocery store and across the street from the post office, with its back to the river. At one point, Wilcox and Bishop went to Spokane to discuss the site with an engineer. “He said ‘Don’t touch it. It’ll bury you,’” remembers Bishop. “I remember coming home we were quite disheartened. Then one day I’m sitting in the office working, and my secretary says, ‘Michael’s on the phone.’”

Low-barrier Environmental Assessment Resolves Uncertainty

Then-Mayor Michael Echanove (2001–2019) thought he had found a way forward for the Palouse Producers site: the municipality would take the wheel, use brownfields grants to assess the site, buy it, and clean it. Then someone else would turn it into something great. Brownfields are properties that are contaminated or perceived to be contaminated. They have latent value, but successful redevelopment requires targeted investment, often both private and public. State and federal brownfields programs act as catalysts and fill initial gaps with funding and technical assistance.

Palouse’s first stop was the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Brownfields Program, where the city availed itself of a targeted brownfields assessment (TBA), a low-barrier technical assistance tool that allowed the EPA to assess the Palouse Producers site on the city’s behalf. The TBA had several of the benefits of a federal grant with little of the paperwork. And because the property didn’t change hands, the city was able to understand the existing contamination without incurring environmental liability.

Between 2006 and 2008, EPA awarded Palouse two TBAs worth $96,500. These produced environmental site assessments that documented soil and groundwater contamination by petroleum hydrocarbons, benzene, and metals. This was a big step forward. Now the question was how to clean it up.

Coming to Terms, Building Trust, and Moving Forward

Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology) hydrogeologist Sandy Treccani could see a path forward for the Palouse Producers’ site using a tool called a prospective purchaser consent decree (PPCD). PPCDs weren’t new in Washington, but they also weren’t common—between 1991 and 2015, Ecology had executed perhaps 25. Under a PPCD, the city of Palouse would take ownership of the Palouse Producers site, assume liability for the contamination, and clean it up. In return, Ecology would provide cleanup funding, and upon completion, the city’s liability would be settled with both the state and third parties—a significant benefit. The deal would produce a clean site for Ecology and a new opportunity downtown for Palouse. The technical requirements were clear, but the equation hinged on very human factors. “It’s a leap of faith,” says Treccani. “They have no reason to trust us. None. In fact, that might be where many small communities start. And it’s the biggest hurdle. Once you have a success, then people can trust you.”

For a seasoned municipal attorney like Stephen Bishop, the rub lay in the small print. Negotiating with the Washington State Attorney General’s office, which served as Ecology’s attorney, Bishop wanted an escape clause, wherein Palouse would be responsible for cleanup only if it received the promised grants. The state couldn’t agree to those terms. The agreement hung in the balance. And then one day, “I was working in the orchard, and I thought, ‘At some point in your life, you have to go on blind faith. In the end, [the state] has all the teeth, but it’s not going to take a bite just to push somebody around,” remembers Bishop. The city could make this work and the wheels began to turn.

In 2009, Ecology awarded the city an integrated planning grant (IPG). It was a “try before you buy” brownfields resource: requiring no local match, the IPG funded environmental assessment, community engagement, and planning for site reuse—all without the requirement to own the target site. The IPG built on EPA’s TBAs, and Ecology chipped in additional funding for assessment in 2010. Now it was time for the city to take ownership and start cleanup.

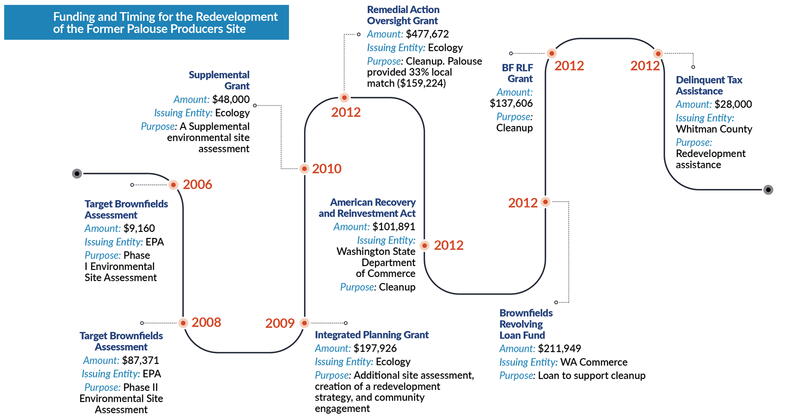

In a series of highly coordinated moves between Ecology, the attorney general’s office, and the city, the state produced a cleanup action plan and the PPCD and conducted the required public comment in the exceptionally rapid timeframe of less than three months. Everything had to come together precisely to extract the property from bankruptcy court, transfer ownership to the city for $1, activate the PPCD, and award grants. Cleanup funding came from state and local sources, and the city also received a low-interest loan from Washington’s brownfield revolving loan fund, managed by the state’s department of commerce. Whitman County chipped in by forgiving back taxes (see Figure 1). The total cost of assessment and cleanup was about $1.46 million.

Over almost two years, the cleanup demolished two buildings and removed the top eight feet of all petroleum-contaminated soils, enough to fill 280 dump trucks. The most contaminated, highest risk soils were hauled offsite, and others were capped in place. The cleanup also removed a previously unknown 500-gallon storage tank. The excavated area was backfilled with clean, compacted fill capable of supporting buildings, and Ecology installed three wells to monitor groundwater, which are still tested biannually as the remaining hydrocarbons continue to degrade. An environmental covenant ensures that future site users are aware of residual contamination and the need to protect the environmental remedy. When the literal dust had settled, “We had a beautiful patch of dirt,” reports Echanove.

Throughout this process, the city’s brownfields advisory committee (BAC) had held regular community meetings to explain what was happening at the Palouse Producers site. Doug Wilcox chaired the BAC, which had six to eight members, including current Mayor Tim Sievers (appointed 2021). With the cleanup complete, the site’s future came into focus. The city was poised to influence its reuse. What did the community need?

Opinions varied. While one side of Main Street backs up to the Palouse River, few sites provide river access, which was important to residents. They also wanted commerce—places to eat or shop that would bring people back downtown and make Palouse a better place to live. Armed with community input, the city solicited proposals from development teams. They received four responses, and selected one from a local team of four friends that included a police officer and a pharmacist. They had proposed a brewery and a veterinary clinic. “What a great proposal to have a vet clinic that was working out of a one-car garage bring their tax dollars into the city,” reflects Mayor Sievers. “And then to have the brewery come in! It’s been a long time since we’ve had a brewery in Palouse.”

The city sold the site to the local development team for $3,000 in 2019. “The committee focused on the site not as a profit center, but as part of Palouse’s future,” says Echanove. That approach made the difference for the development team because it made the site accessible. Asked how other cities could find similar partners, investor Joe Handley said, “You have to find somebody who loves the community, is in the community, and is not in it for the money. We’re in it for the long run.”

New Life and Good Beer

Now home to TLC Animal Care, the vet clinic was the first building to go up, opening in June 2022. Dr. Andi Edwards grew up in Palouse and trained at nearby Washington State University’s renowned veterinary school. “I remember being a kid and walking past the scary old gas station. I thought it was great when they cleaned it up. It was good for this town, good for the environment, and good for the river.” When the opportunity at the former Palouse Producers site presented itself, she had been working out of her basement for seven years, outside Palouse city limits. Dr. Edwards designed the clinic herself, and while construction paused during COVID, community enthusiasm didn’t: community members covered the drywall in messages of support. “Our building is literally full of community spirit,” says Dr. Edwards.

Today, TLC Animal Care serves people across a roughly 50-mile radius with exam, dental, and surgery facilities. For Dr. Edwards, her clinic is the realization of a multiyear dream, and a chance to give back to her hometown in a significant way. “[The former Palouse Producers site] was an awesome opportunity for a small business owner. And we were happy to bring our taxes into the city,” she says. She employs four technicians—two of whom she had to hire within the first few months of opening to keep up with demand—and a weekly relief doctor.

With the clinic up and running, the Palouse Brewery got under construction, opening in January 2023 to a line out the door and standing room only. “We had people from all walks of the community,” relates Handley. “People who would never talk to one another were standing shoulder to shoulder having a beer. We wanted a place where everyone feels welcome, and we did it.” With four of their own beers on tap and plans to expand to six, the brewery uses local products wherever possible, like garbanzo beans for its falafel. It employs 12 people, and there are plans to eventually can and distribute Palouse Brewery beer in Washington and Idaho.

One of the most exciting things about the redevelopment project is the access it provides to the river. At the brewery, people can sip beer and watch the water roll by. “Everyone’s going to be down here watching when the river gets high,” relates Mary Welcome, a community organizer, former city councilmember, and member of the Chamber of Commerce. The vet clinic also has a small grassy yard facing the river. “We sit out there a lot,” says Dr. Edwards. “We do a lot of end-of-life care, and people find that space really meaningful.”

Ripple Effects

In late 2020, Spokane investors David Birge and David Griswold bought the old school gymnasium next door to the former Palouse Producers site. Built prior to the Great Depression, the vacant two-story brick edifice backed up to the river. How did they end up in Palouse? “We liked the down-to-earth feeling,” says Griswold. “When you see a busy street in a small town, it’s notable,” adds Birge. “And the city council seemed pretty progressive. They want to see the city prosper.” The old gym is today home to a bank branch and a health clinic—a significant development, given that the last bank left town in 2020.

It has taken years of focused, patient work to get here, but Palouse’s main street now has four new businesses housed in three buildings, two of which are new and one of which was previously vacant for years. “The city’s role was just trying to open the doors for opportunity,” says Mayor Sievers. For Ecology’s Sandy Treccani, Palouse’s success is a testament to the power of partnership: “Build trust and relationships,” she advises. “You can’t build your house until you build the foundation.” For Joe Handley, that rings true: “Everyone involved has been incredibly helpful…. The Department of Ecology really wanted this, and really helped us make it happen…. You could tell they were really invested in it.” For Welcome, the big lesson is clear: “Public funding and public infrastructure make opportunities that the actual public can access,” she says. Echanove sums it up: “Brownfields properties are awesome properties.”

SARAH SIELOFF is an urban planner and funding strategist at Haley and Aldrich.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!