This is the third in a three-article series about high-crime places. Access the first article here and the second article here.

A Store Robbery Problem

In the 1980s, violent crime surged, and convenience store robberies were particularly troublesome. Research noted that some convenience stores were particularly vulnerable—those with windows covered with advertisements and staffed by a single clerk, for example.

In July 1986, following a spate of convenience store robberies, the Florida city of Gainesville passed an ordinance mandating specific robbery prevention actions at all city convenience stores: keep windows clear so passersby can see in, situate the point-of-sales terminal so it is visible from the street, reduce cash available and post signs informing would-be robbers that the store has little cash to be taken, upgrade lighting in parking areas, install security cameras, train night clerks in robbery prevention, and require two clerks after dark. A comparison of the year before and the year after these requirements went into effect showed a 65% reduction in convenience store robberies overall and a 75% reduction in nighttime robberies.

In previous articles in this series, we described place-by-place problem-solving. Gainesville took a different approach. After a careful analysis of the convenience store robbery problem—including examining local data, studying cities that had regulated convenience stores, reviewing research on the topic, and consulting with convenience store owners—Gainesville took a regulatory approach. It would regulate all 47 of its convenience stores. The use of regulation to reduce crime at places is our subject in this article.

Regulation of Crime Places

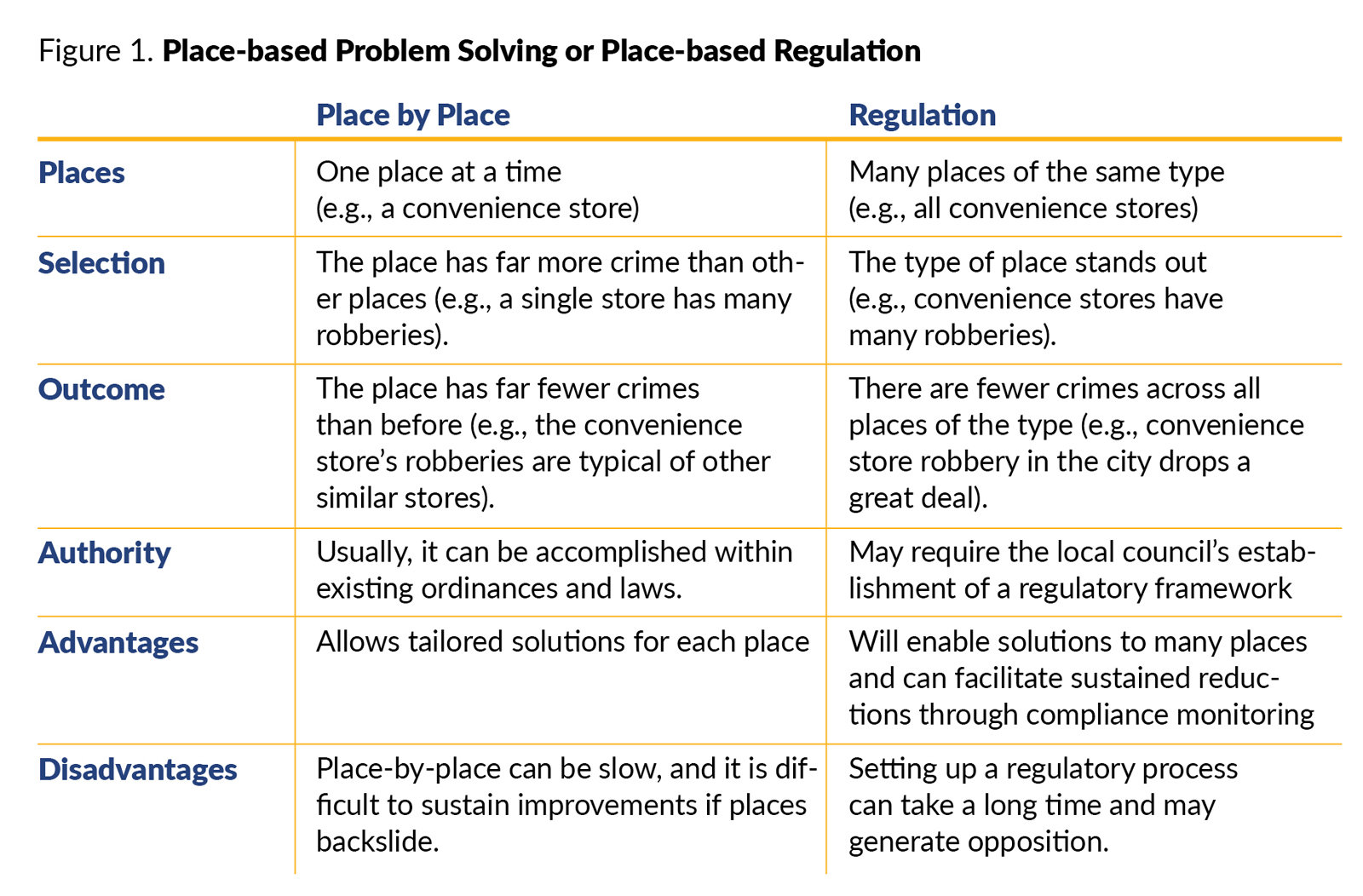

Regulation has an advantage over place-by-place prevention; it can facilitate crime prevention at multiple places simultaneously (see Figure 1). When a particular type of place (e.g., bars, apartment buildings, parking garages, motels, or convenience stores) is contributing to the local jurisdiction’s crime load, and each place of that type has standard features that increase its vulnerability to crime, then regulation makes sense. With convenience stores in Gainesville, these conditions were met. So, instead of working with each store individually, the city decided to regulate all convenience stores to reduce robberies.

Means-based Regulation

If Gainesville in the late 1980s had one, two, or three convenience stores where most of the robberies occurred, then the place-by-place approach we discussed in earlier articles would have made sense. Substantial reductions in robberies at extreme robbery stores would have addressed most of the convenience store robbery problem. But Gainesville’s convenience store robberies were only mildly concentrated. About half of the 234 robberies over five years were at 12 stores (with eight or more robberies each), but only two stores had zero robberies during this period. And, 38 stores had two or more robberies over the five years. Although a few stores seemed particularly robbery-prone, most stores had robberies. Therefore, it made sense to tackle the problem by regulating all stores rather than addressing it one store at a time.

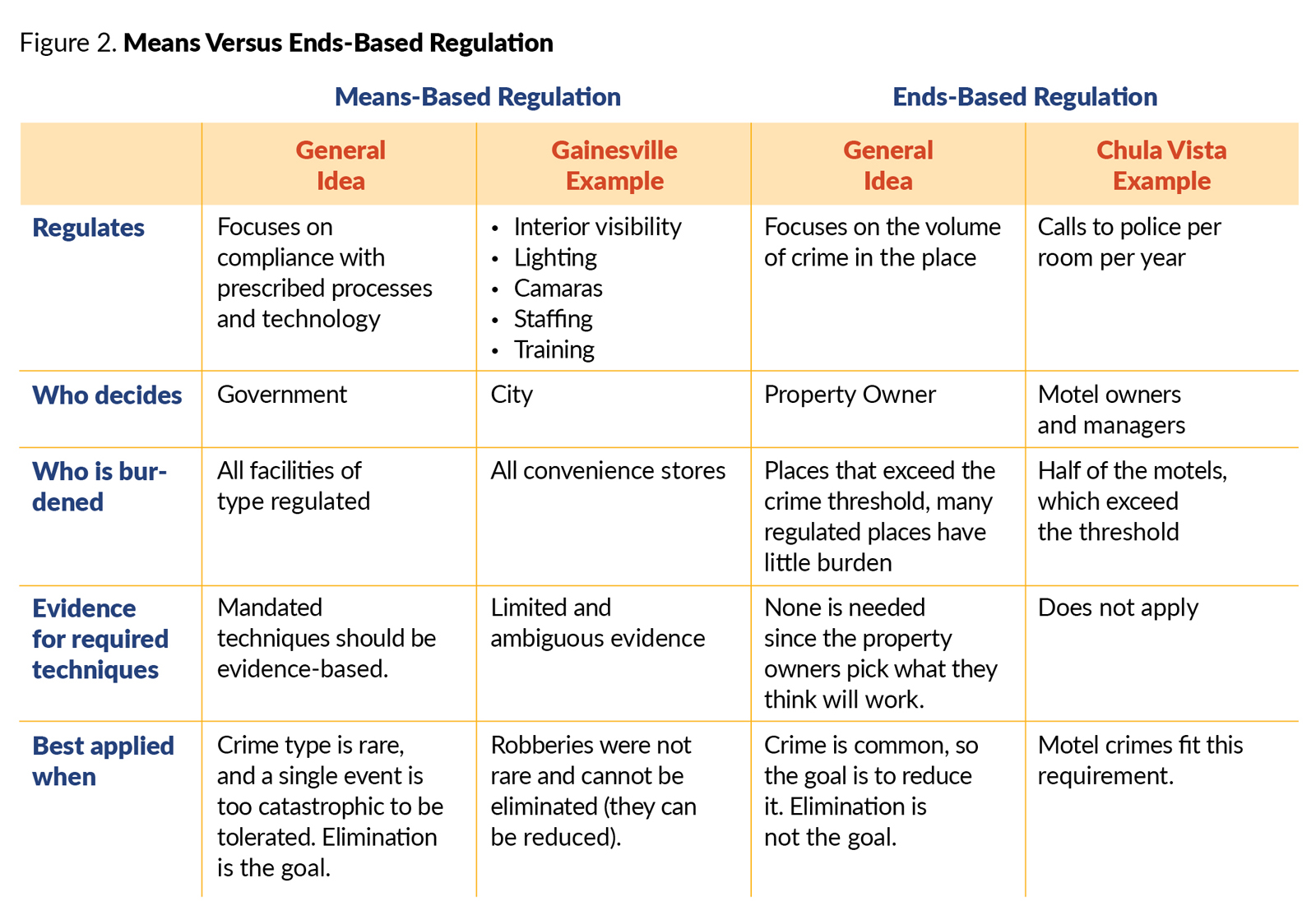

The type of regulation used in Gainesville is sometimes called means-based regulation. Means-based crime-place regulation has two features, as Gainesville illustrates. First, it requires compliance with rules governing how places are managed. In Gainesville, these include restricting the amount of cash available to robbers, improving lighting and surveillance, and mandating that two clerks be on duty after dark. Second, all places of a type have to comply. In Gainesville, the regulations affected all convenience stores: the store with 14 robberies was affected just as much as the two stores with zero robberies.

There are four limitations to means-based regulation. First, there is often limited evidence that the required prevention methods will work. Second, the city or county will have to inspect all regulated places to ensure compliance, thus increasing business and government costs. Third, businesses will have difficulty substituting more cost-effective prevention tactics for the mandated prevention. Fourth, compliance does not guarantee crime reduction, as it can be superficial. These limitations make it more likely that regulated businesses will vigorously oppose enabling legislation proposed by city or county officials.

Fortunately, there is a second form of regulation that can overcome these limitations.

Ends-based Regulation

In the early 2000s, the city council of Chula Vista, Southern California, grappled with the high volume of calls to police from motels. Police were ripping through tax dollars handling these calls despite police efforts to get motel owners to improve crime prevention at their places. The police crime analysis unit had undertaken an in-depth analysis of the problem. Among the many facts they uncovered was that the bulk of the calls came from a small number of the city’s 24 motels. The most troublesome motels were not concentrated in a single bad area; they were scattered, often near non-troublesome motels. This was, like most crime problems, not a neighborhood problem, but a place problem.

The solution recommended by the police and adopted by the city council was to regulate motels. The city used an ends-based regulatory approach by enacting a permit-to-operate ordinance for motels. All motels required an operating license from the city. To maintain that license, a motel had to keep its number of calls to the police to no more than 0.61 calls per room per year. The police chose this number because it was the median call rate—half the motels fell below it, so those motels were automatically in compliance. 1

Within a year of creating this regulation, all motels were below this threshold, though a few struggled to remain in compliance. An evaluation by researchers at California State University–San Bernardino showed a 70% reduction in motel crime following the regulations, with the biggest reductions among the few motels causing the most trouble.

Chula Vista had applied a form of ends-based regulation of crime places. The city did not tell motels how they should operate their businesses (as occurred in Gainesville with convenience stores). Instead, the city set a limit on how many calls a motel could generate to keep its business license. Many of the motels were comfortably under this limit, so the regulations had little impact on them. A few hotels were above the limit, but not terribly above. They had to make some changes. And a small number of motels (about four) were far above the limit. They would have to make big changes. Although the police department suggested crime prevention changes to the motel owners, it was the owners who had the ultimate choice of what to do.

End-based regulation focuses on outcomes. This allows the managers of regulated places to decide what they need to do to comply. And for most places, they have to do little or nothing. So, the burden of the regulation falls on the most crime-prone places. Compliance can be easily verified without site visits: examine police reports.

Ends-based regulations overcome the limitations of means-based regulations. First, because ends-based regulation does not mandate specific prevention techniques, it does not require the government to guarantee a mandated technique’s effectiveness. Second, compliance monitoring is easier because the police do not have to visit the places, just count crimes reported from them. Third, businesses pick the prevention techniques that work best for them rather than having to implement a standard technique that might not fit. And fourth, because compliance locks in crime reduction, superficial compliance with mandated techniques is no longer an issue. These advantages may make ends-based regulation more palatable to regulated businesses.

Nevertheless, there are limitations to ends-based regulation. It should not be used when the crime of concern is so severe that no occurrences are tolerable. We would not use it to prevent school shootings or aircraft hijackings, for example. For these sorts of crimes, means-based regulation is the better option. Ends-based regulation is best used for ordinary, high-volume crimes where there is little expectation that they can be eliminated entirely. Another limitation is that ends-based regulation requires a relatively error-free crime reporting system. We would not want crimes to be misattributed to regulated places, nor would we want crimes at these places to be mistakenly unattributed to the regulated place.

There are many forms of end-based regulations. A city could charge fees or impose fines if demands on police exceed a defined limit. Another city could not send police to the place once the regulatory threshold is reached (for example, a retail store who refuses to implement crime prevention measures and instead calls the police almost daily about minor shoplifting). A city or county could even mix ends- and means-based regulation: below a threshold, the means a place uses to stay in compliance is up to the place manager, but if the place is persistently above the threshold, then the jurisdiction mandates particular means for keeping crime down. It’s also important to consider the crime types occurring and potential harms. Many cities that have passed ordinances to address excessive calls to police, for example, will have exemptions in place for certain types of calls (e.g., domestic violence) so as not to discourage the reporting of personal violence.

Conclusions

For city/county managers desiring to drive down crime, a place-based approach is often a useful strategy. In this and our two previous articles, we have listed three options. First, for situations where crime is highly concentrated at a very few places with little in common, a place-by-place problem-solving approach may be best. If places of the same type are vulnerable (as was the case in Gainesville and Chula Vista), then a regulatory approach is worth considering. For high-volume crimes, an ends-based approach may be useful as it focuses directly on crime reduction, allows easy compliance monitoring, and permits place managers to tailor their solutions to be in compliance. If the crimes are severe, so that a single occurrence is intolerable, a means-based approach is probably the best option.

SHANNON J. LINNING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada.

TOM CARROLL, ICMA-CM, is city manager of Lexington, Virginia, USA.

DANIEL W. GERARD is a retired 32-year veteran (police captain) of the Cincinnati Police Department, USA.

JOHN E. ECK, PhD, is an emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, and a lecturer at the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, USA.

Endnote

1Bichler, G., & Schmerler, K. (2020). Crime and disorder at budget motels in Chula Vista, California. In M.S. Scott & R.V. Clarke (eds.), Problem-Oriented Policing: Successful Case Studies (pp. 201-213). New York, NY: Routledge.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!