Since the early history of public administration practice and research, the question of the appropriate political and administrative roles of managers has been debated. Since then, although there is now widespread recognition that a true politics-administration dichotomy is impossible in practice, there remains a lack of consensus about what the “political” role of the manager looks like.

Local government managers, perhaps more than any other public managers, have a broad array of responsibilities and engage with a broad set of stakeholders. As such, this question is of particular importance to local government managers. This article will provide some historical context for this debate and will discuss the importance of the manager’s role in the policy process.

Brief Historical Background

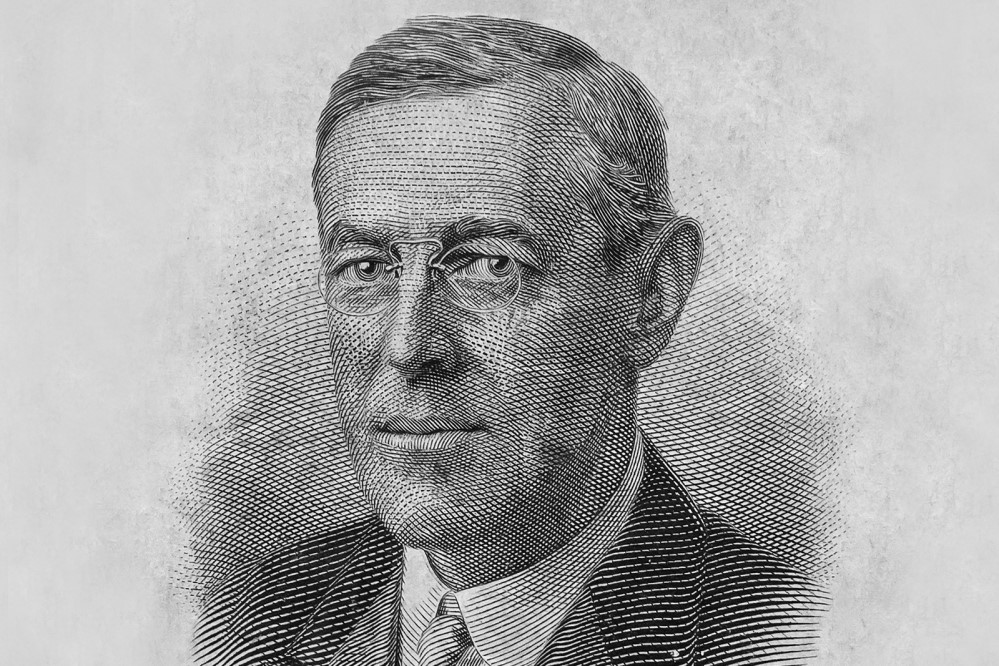

Nearly everyone who has a degree in public administration has learned about the politics vs. administration dichotomy. Woodrow Wilson, who earned a Ph.D. in political science long before he would be elected president of the United States, wrote a seminal work on this topic, “The Study of Administration”.1 In this article, Wilson argued for a separation of politics and administration, but he also stressed that administrators should have “large powers and unhampered discretion.” He asserted that “the ideal for us is a civil service cultured and self-sufficient enough to act with sense and vigor, and yet so intimately connected with the popular thought, by means of elections and constant public counsel, as to find arbitrariness of class spirit quite out of the question.” Still, later scholars interpreted Wilson’s argument as advocating for a complete removal of public managers from the policy process; and this philosophy influenced the education of practitioners. In local government management, this was interpreted to mean that the manager was a neutral expert who would not provide policy advice to the elected body.

Local government managers have always known this was unrealistic. In our historical analysis of the policy and administrative roles of managers, James Svara and I found acknowledgements by city managers in the early 1900s of the importance of these policy roles.2 As stated in the Second Model City Charter, the manager should “show himself a leader, formulating policies and urging their adoption by council.”3 While the visibility of the manager in the policy process has changed over time and the manager’s role in the community has expanded, the expectation that the manager should be involved in the policy process has been a constant since the birth of the profession.4

Why has the Dichotomy Persisted?

Recently, I heard a seasoned manager, who was speaking to a group of new and aspiring managers, tell the audience that he never provides policy advice to his council. This is a simple example of how the conception of a dichotomy between politics and administration persists in local government management practice.

Wilson’s article has been interpreted without considering the context of the time in which he was writing. He was arguing for a “science of administration”; that public administration was as worthy as a field of study as any other. He did advocate for a separation of politics and administration; however, Wilson’s concern was with the encroachment of partisan politics in the administrative process rather than administrators encroaching on policy. In his 1885 book, Congressional Government, Wilson was concerned with both the corrupting and politicizing interference of party organizations in administrative affairs and also the excessive attention by Congress to administrative matters. Congress, Wilson wrote, “set itself . . . to administer government.”5

Even during the period that followed, when some scholars advocated for a pure separation, others argued that would not be feasible or advisable.6 And yet, there are still practicing managers who have been taught to stay out of the policy process even though doing so would violate the ICMA Code of Ethics, Tenet 5:

Submit policy proposals to elected officials; provide them with facts, and technical and professional advice about policy options; and collaborate with them in setting goals for the community and organization.

James Svara has written extensively on how and why the myth of a dichotomy persisted.7 He states that it “is convenient to explain the division of roles in terms of total separation because it is easier to explain than a model based on sharing roles.”8 Svara also argues that accepting the idea of a separation of policy and administration allows elected officials to blame administrators for unpopular decisions. Despite the persistence of the dichotomy, the manager’s role in the policy process is a legitimate one.

The Role of the Local Government Manager in Policymaking

The values of the local government management profession, as codified in the ICMA Code of Ethics, prohibit managers from engaging in activities that are political in nature, particularly those related to partisan politics. Local governments exist in a system that is awash in politics and drawing distinctions between appropriate and inappropriate activities may be challenging at times. Complicating this reality is the fact that local government managers come to their positions from different educations, regions, and mentoring experiences that shape their belief system and manner of practice. Managers must also take on roles that are consistent with the expectations of their elected officials.

In practice, the policy and administrative roles of local government should be shared between the elected officials and the manager. James Svara suggested a model called “complementarity” to explain this relationship.9 In order for local governments to function well, elected officials need to receive high-quality policy advice from the manager and staff. Managers tend to have a longer time horizon for policy consideration, they are familiar with effective policies used in other local governments, and they possess expertise that can inform the assessment of policy choices. Likewise, while elected officials should not be engaged in the day-to-day operations of government, their oversight responsibilities and their role in establishing the vision for the community, are critical for the success of the local government. The balance may shift somewhat depending on the preferences, skills, and personality traits of those holding office.

A few years ago, Public Management published an article that explained the “Flight Analogy” graphic designed by Mike Baker in Downer’s Grove, Illinois.10 Mr. Baker created the graphic to help his council understand the shared policy and administrative roles of elected officials and staff. It is an excellent illustration of the concepts discussed in this article. See Figure 1.

Managers and elected officials should work together to find the appropriate balance of administrative political roles for their organizations and communities. One of the arguments for the council-manager form of government is the expert, nonpartisan policy advice that the manager provides to the council. This expert advice is necessary for a high-performing local government organization.

KIMBERLY NELSON, PhD, is a professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Endnotes and Resources

1 Wilson, Woodrow. 1887. The Study of Administration. Political Science Quarterly 2(2): 197-222.

2 Nelson, Kimberly L. and James H. Svara. 2014. The Roles of Local Government Managers in Theory and Practice: A Centennial Perspective. Public Administration Review 75(1): 49-61.

3 Woodruff, Clinton R. 1919. A New Municipal Program. New York: D. Appleton and Co.

4 Nelson and Svara 2014.

5 Wilson, Woodrow. 1885. Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

6 Svara, James H. 2001. The Myth of the Dichotomy: Complementarity of Politics and Administration in the Past and Future of Public Administration. Public Administration Review 61(2): 176-183.

7 Svara 1998; Svara 2001.

8 Svara 2001: 177.

9 Svara 2001.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!