As the United States has grown and the quality of the nation’s housing has improved, it has also become more expensive and less affordable to much of the nation’s population. Millions of Americans today find themselves spending so much for housing that they have difficulty meeting other necessities of life, while many others are thwarted in their dreams of homeownership.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the crisis in housing affordability has been a recurrent theme in the media, while solutions have been put forward by organizations and people across the political spectrum. But much of what is written about the problem is often misleading, while the solutions being most widely promoted would have little or no effect on the families most severely affected. In this article, I will describe the elements that make up the affordability crisis, and why they have just recently become so much more severe. Then I discuss the current efforts to address the problem and suggest what may be needed if it is ever to be truly resolved.

1. Breaking Down America’s Affordability Problems

There is no one affordability problem. There are many affordability problems, depending on one’s income, where one lives, and whether one is an owner or tenant. The most important, though, in terms of the suffering it causes and its significance for housing policy, is rental affordability or cost burden. It affects people of different incomes differently and varies greatly across the United States. A second problem is homebuyer affordability, or the extent to which high housing costs prevent households from becoming homeowners, but which mostly affects families of higher incomes than those whose lives are most deeply blighted by high rental costs. Most of this article will focus on rental affordability.

Households spending more than 30% of their gross income for rental costs, including utilities, are considered cost burdened. Those spending more than 50% of their gross income for rental costs are considered severely cost burdened. In 2021, 21.6 million renter households, almost half of all American renter households or one in six American households, were cost burdened. More than half of those, or 11.6 million renters, were severely cost burdened. The great majority of these households were very low-income households. While the percentage of cost burdened renters dropped slightly between 2014 and 2019, it has risen sharply since then. Two distinct and separate affordability problems, however, are nested in this total. I call them systemic cost burden and strong-market cost burden. They are very different.

Systemic Cost Burden

Very low-income families face the most severe rental affordability problems. They must contend with a systemic imbalance in the nation’s economy between what low-level jobs pay and what it costs a private landlord to provide a modest but decent rental dwelling unit. For example, the 25th percentile hourly wage (25% earn less and 75% earn more) in the United States for retail workers in 2021 was $12.43/hour. A worker in such a job, working 35 hours/week for 50 weeks (if she’s lucky) will earn a total of $21,131 for the year. If she is the sole support of her family, she can afford to pay no more than $528/month for rent without being cost burdened.

Most rental properties in most American communities are either single family homes or a small multifamily buildings. When you add up the operating costs, including maintenance, reserves, property management, taxes, insurance, water and sewer fees, and allowances for vacancies and collections, they typically run between $400 and $600 per year. Assuming the landlord’s cost to acquire and upgrade the property is a modest $100,000 and she aims for a 6% annual return on her investment, or has to pay a mortgage at that interest rate, the lowest rent they can charge and still come out ahead is $900 to $1100 per month, almost double what the 25th percentile retail worker and her family can afford.

Severe cost burden is concentrated among America’s poorest families. Of these families, 87% of renter households earning under $10,000/year and 67% of those earning $10,000 to $19,999 spend 50% or more of their gross income for housing. The poorest 20% of renters account for 60% of all households with severe cost burden. These families live in chronic instability. They struggle to pay for food, transportation, and other essentials, while their ability to pay their rent can easily be derailed by unexpected medical expenses or a car breakdown. Cost-burdened households, particularly single mothers with children, are at greatest risk of eviction. They move more frequently than other families and often experience episodes of homelessness, undermining their family life, their children’s future, and their neighborhood’s stability.

Strong Market Cost Burden

Systemic affordability problems exist everywhere in the United States. But in high-demand housing market areas like coastal California, New York City, or Washington, DC, the pressure created by strong demand and limited supply leads affordability problems to migrate upward; that is, families at progressively higher income levels experience affordability problems. Renters earning between $30,000 and $74,999 (roughly 40 to 100% of the national median) are much more likely to be cost burdened in Los Angeles than, say, in Philadelphia or Cincinnati. These renters are hurting, but the amount of money a family earning $75,000 and paying 40% of their income for rent has left over for other necessities is far greater than that available to the family earning $20,000.

Strong-market affordability flows from two intersecting problems: the cost of housing has been bid up by demand from more affluent households and is made worse by the difficulty and high cost of building in these areas. Housing production in areas like Los Angeles or San Francisco is severely constrained not only by restrictive regulations but by many other factors, including natural and environmental constraints. Those constraints, along with extremely high land costs, the high cost of labor and materials, and the effects of rigorous building and safety codes, have led the cost of building to skyrocket. A 2022 report pegged average construction costs in San Francisco at $439 per square foot. Using this construction cost, adding modest land and soft costs, a small new two-bedroom apartment would cost over $750,000, and would have to rent for over $4,000/month to break even. While building enough of those apartments might lead older buildings to filter down in price to where some middle-income families could afford them, tight land supply means that building enough to make a major difference might be well beyond what is realistically possible in San Francisco and many other supply-constrained strong market areas.

Affordability and the Ability to Buy a Home

Most American families aspire to homeownership. While for many years house prices and household incomes tended to move in parallel, starting around 2000 (except for a dip during the Great Recession) house prices have been rising faster than incomes. In addition to the price of the home, though, a family’s ability to afford a home depends on the interest rate on the mortgage, as well as the size of the down payment and the annual cost of property taxes, insurance, and other fees, which vary widely from one part of the United States to another. To measure this, the National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo have created a Housing Opportunity Index (HOI), which combines incomes, prices, and interest rates to estimate what percentage of the houses in any given housing market area are affordable to a family earning the median income for that area. The lower the HOI, the fewer homes that are affordable to such a family. See Figure 1.

The HOI goes up and down. Affordability dropped during the 2000–2007 housing bubble, rose sharply during the Great Recession, and stayed fairly stable between 2013 and 2020. Although house prices were rising during these years, their effect was mostly offset by dropping mortgage interest rates, which bottomed out in 2020. The steep drop in affordability since 2020 comes partly from rising prices and partly from rising interest rates. As with rental affordability, the affordability of homes for sale also varies widely across the country. There are areas where almost all homes are affordable to a median-income household (like Cumberland, Maryland or Elmira, New York) and those where hardly any are affordable (like Orange County, California). The 11 least affordable housing market areas are all in California, while of the 40 areas (out of 234) where a median-income family can afford 75% or more of the homes, 39 are in the Northeast or Midwest.

The ability of middle-class families to buy a home fluctuates widely over time and geography. Within 15 years, the HOI has yo-yoed from 40% to 80% and back to 40%. But there are still many places in the United States—although not necessarily those where most people want to buy homes—where homes are highly affordable. As we turn to the way the perception of affordability as a metastasizing crisis has grown seemingly overnight, it is important to maintain that perspective.

2. COVID and the Unexpected Crisis

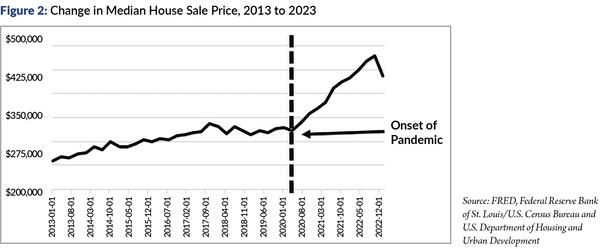

While housing affordability has long been seen as a problem, it took on new urgency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soon after the onset of the pandemic in early 2020, rentals and sales prices both began to rise much faster than ever before, even more than during the height of the bubble years. From the second quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2022, the median sales price for homes in the United States rose from $322,600 to $479,500, or nearly 50%. Although prices then began to tail off, the recent decline has been more than offset by rising mortgage interest rates. Rents also increased, by 13.5% in 2021 alone. While sales prices and rental growth are slowing down, they will likely never return to pre-pandemic levels. What can account for this increase, which was largely unpredicted by either researchers or industry professionals?

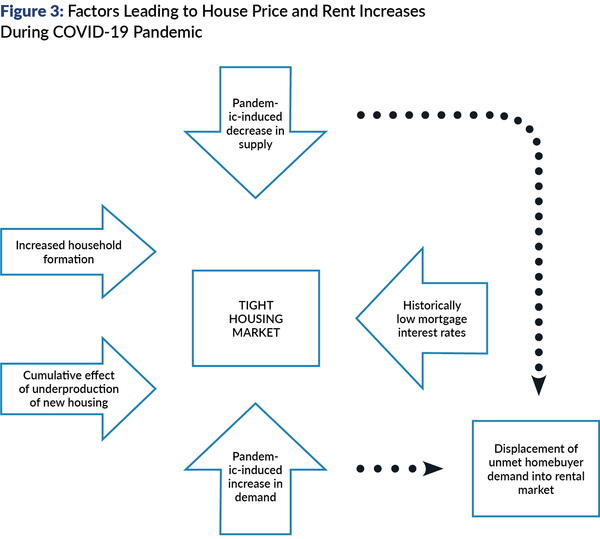

Many different factors came together in 2020 to create the conditions for sharp price and rent increases, as shown in Figure 3. New housing production has lagged behind demand since the onset of the Great Recession, creating a cumulative shortfall in supply, while new household formation, the main driver of housing demand, which was sluggish for many years, increased significantly during the late 2010s. At the same time, mortgage interest rates, which had been gradually declining since the 1980s, bottomed out at 2.66% in December 2020.

On top of this, the pandemic triggered both even greater demand and even less available supply. Many affluent renters realized that low mortgage interest rates made homeownership more attractive than continuing to rent. With people working from home rather than commuting to an office, many began to look for larger quarters, while others chose to relocate to communities farther from their workplace. Cities two or three hours from Manhattan—like Kingston, New York, or Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; or with strong natural amenities like Provo, Utah, or Sarasota, Florida—experienced sharp demand surges. The increase in demand was strongest among high-wage, upper-income households, disproportionately pushing prices upward.

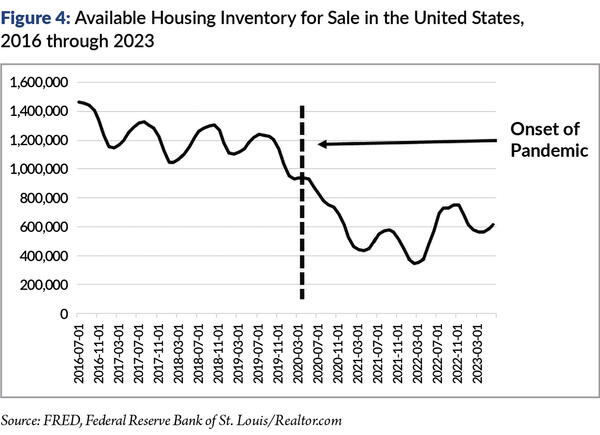

At the same time, the number of homeowners putting their houses on the market dropped sharply. Many reasons have been suggested for this, including older owners’ reluctance to move or have strangers in their homes during the pandemic. As the market further tightened and mortgage interest rates began to rise, owners holding cheap mortgages realized that moving could mean much higher housing costs. Whatever the reasons, available housing inventory, which is highly seasonal, failed to rise as usual during the spring and summer of 2020, and then dropped precipitously during the second half of the year, just as demand was rising. By mid-2023, although the pandemic is no longer driving people’s behavior, inventory levels have remained far below pre-pandemic levels.

The increase in house prices and rents, however, has inserted the issue of affordability squarely into the American political mainstream. But what does that really mean for the millions of people impacted by high housing costs?

3. Can We Solve the Affordability Problem?

Housing costs have been on the national agenda for a long time. In 1978, the federal government created a Task Force on Housing Costs, whose final report opens by noting, “The high cost of housing is now a major problem for millions of Americans.” In 1990, President George H. W. Bush convened an Advisory Commission on Removing Barriers to Affordable Housing, while in 2004, president George W. Bush announced the America’s Affordable Communities Initiative to “bring homes within reach of hard-working families through regulatory reform.”

In some ways, nothing is new. But what people are talking about today is different in important ways. For one thing, the focus is overwhelmingly on a single issue: underproduction of new housing. While an undersupply of new housing, particularly in high-demand areas like coastal California, certainly contributes to the affordability problem, it is far from the only contributor to the problem. The focus, moreover, is on one specific obstacle to building more housing: land use regulation. That is, reforming the zoning laws local governments use to regulate the use, density, height, and other features of development.

This focus has brought together an unusually broad coalition, including homebuilders, as well as so-called YIMBY (“Yes in My Back Yard”) pro-development voices from left to right, libertarian tech bros, and left-wing housing advocates. However, the voices of those who argue that other strategies are needed, particularly organizations serving very low-income families, are barely heard.

The strength of the coalition pushing for zoning reform has already led to major changes in many municipal zoning ordinances and in the laws of a number of state governments. The latter is most important, since under the American system of government, state law defines how towns and cities regulate land use. Any change to a state’s zoning laws, therefore, changes the ground rules for hundreds of separate municipal zoning ordinances.

The first notable state zoning change was in Oregon in 2019, when it amended the state zoning law to abolish exclusive single-family zoning in cities over 10,000 in population. All such cities must now allow two dwelling units where only one could be built before, while cities over 25,000 must allow at least four. Reforms have since been enacted in California, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, and Washington. Eight states now require municipalities to allow accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—second dwelling units on the same single family lot, either within the existing house or as a smaller separate structure—in single family zoning districts.

Ending the historic practice of exclusive single-family zoning, meaning zones where only single-family detached houses are allowed, has been a major goal of the zoning reform movement. That restriction governs the great majority of residentially zoned land in the United States, including almost all suburban land and large parts of central cities, including 70% of the residentially zoned land in Minneapolis and 81% in Seattle. Indeed, many people point to the moment in 2019, when Minneapolis amended its zoning laws to eliminate single-family zoning districts and to permit up to three housing units to be built on each individual building lot as the first major victory of the zoning reform movement.

This turnabout on zoning, although still embryonic, must be recognized as a major achievement on an issue that until recently was seen as all but politically untouchable. Yet is it the “solution” to the affordable housing crisis, or even, as has been argued, to homelessness? While some of the reforms will help, usually in small ways, the answer is an unequivocal no. Although the much-heralded Minneapolis reform affects 70% of the city’s land area, after two and a half years it had resulted in only 100 new housing units; put differently, it increased housing production in the city over that time by only 1%.

Part of the problem is that, as I have written elsewhere, there are compelling economic reasons why increasing density in already-built-up single-family districts—which describes almost all urban single-family districts—not only fails to lead to large-scale housing production, but all but dictates that any new housing will be significantly more expensive than the homes it replaces. Indeed, it is hard to escape the conclusion that—leaving aside ADUs, which are truly helpful—rezoning of built single-family areas is more about symbolism than about substance.

Although rezoning of urban commercial or industrial areas for higher-density residential use may be somewhat more productive, zoning reform in heavily developed central cities like Minneapolis or San Francisco is likely to have only a limited effect on housing supply, if only because of the inordinate cost and difficulty of site assembly and the disproportionately high cost of construction, as discussed earlier. If enough new housing gets built, it may have some effect on reducing existing rents through the filtering process, but in most cases the effect is likely to be quite modest.

Increasing housing production in the suburbs is easier and likely to have far more impact. Vacant or underutilized sites, such as low-density strip commercial areas along arterial roads, are widely available and considerably less expensive to develop than urban sites. Rezoning those areas, along with rezoning underutilized office parks to allow multifamily housing, while changing the zoning of as-yet-undeveloped land currently zoned for single family homes, could actually lead to significant increases in housing production.

But the shortfall in housing production is not just a matter of zoning. Many other factors stand in the way of significantly increasing housing production, including non-zoning regulations, the difficulty and cost of site assembly in largely built-up cities, shortages of skilled construction workers and qualified subcontractors, and high barriers to entry for start-up land developers. None of these issues have yet been seriously tackled, and some have hardly been discussed. It is important to remember, moreover, that many regulations, like limits on building in floodplains or wetlands, are there for good reason.

All of this, however, fails to address the most urgent question. At best, a program of extensive zoning reform, coupled with other measures to increase housing production, may help ameliorate the problems of some struggling middle-class households squeezed by high costs and limited supply in high-demand markets such as coastal California and New York City. Even those effects are likely to be limited because of the inordinately high cost of the new housing that will be built. It will not begin to meet the needs of low-income families, whose lives are far more devastated by housing cost burdens, because the systemic gap between housing costs and incomes makes it impossible, however many units we build, for costs to filter down to where those families can afford housing in the private market. Even less will it help meet the needs of homeless people, who (more or less by definition) have very low incomes and who are often further burdened by social, mental, or physical disabilities.

It is widely held that where the cost of an essential public good exceeds the ability of people who need that good to pay for it, the public sector should help bridge the gap. Thus we provide minimum levels of health care and food through Medicaid and SNAP as entitlements for people whose incomes are too low to pay for those goods. But that is not true for housing. Instead of being an entitlement, housing assistance is a lottery. The most widely cited estimate is that only 24% of eligible households in need are able to obtain housing assistance, in most cases through a housing choice voucher, which pays the difference between the full market rent and what a low-income family can afford, while paying 30% of their income for rent. Almost all the other 76% are cost-burdened.

The single most important thing we can do to solve the affordability crisis among low-income families is to provide a housing allowance—whether through the current voucher program or a redesigned and improved program—for every household whose income is too low for them to afford modest but decent housing in the private market.

In many communities, where supply is adequate and prices relatively low, a well-designed entitlement housing allowance program might in itself largely address the affordability problem. In higher-priced strong market areas, it would have to be combined with a program to subsidize construction of affordable or mixed-income housing to provide an adequate supply of moderately priced dwellings where people could use their allowance, including supportive housing for homeless people. This would be expensive, but well within the means of the federal government. It would be a small part of what we currently spend on Medicaid and might well reduce Medicaid costs by improving family health in the bargain. Even then, however, it would have to be a regional, not a local program. Given the cost and scarcity of building sites and the exorbitant construction costs, it is hard to see how some cities like San Francisco could ever create enough housing to meet the needs of their lower-income residents.

This is not an either-or proposition. Zoning reform is long overdue, and recent reforms are a good step forward. But they address only one small piece of what is a complex systemic problem. Treating it as the solution is not only dangerously misleading, but ignores the urgent needs of millions of low-income families for whom zoning reform by itself is little more than a cruel hoax.

ALAN MALLACH is a senior fellow at the Center for Community Progress, Washington, DC.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!