By Irv Katz

Connections between generations have been at the core of community since the emergence of humankind. Yet, life in most developed countries has shifted from parents, children, grandparents, and other relatives living under one roof—or even in the same neighborhood or town.

Industrialization, mobility, prosperity, and other factors made it possible, even desirable, for young adults to move out and start their own lives and then their own families, sometimes in a nearby geographic area but often many, many miles away.

Older adults who cannot or choose not to remain in their homes find a range of housing options, some of them restricted to people over a certain age and without children.

The organization I work for, Generations United, and others in the intergenerational space—researchers, advocates, philanthropies, public officials, business leaders, service providers, journalists, among them—raise the issue of intergenerational connections not out of a sense of nostalgia for the extended family or ideology but because the generations are interdependent and need one another to thrive and survive.

When learning and caring for one another does not occur across generations, people do not fare as well and the additional burdens of learning and caring, particularly among the more vulnerable among us, become costs to society—costs in terms of problems and social needs that now become the responsibility of the public and nonprofit sectors.

In other words, we pay a steep price for generations not being connected and providing at least some of the functions extended families and connected communities once did. Extended families and close communities took in and helped members experiencing rough times; lack of extended family and community leaves those in crisis to depend on government and charities.

Benefits of Connections

Some researchers come at the issue from another vantage point: the effects of intergenerational connections and experiences on children, youth, and older adults. These effects have been found to be positive and beneficial.

There is compelling research on the subject, nationally and internationally. Some of the key conclusions of this research are cited in a 2017 report issued by Generations United and the Eisner Foundation, I Need You, You Need Me: The Young, The Old, and What We Can Achieve Together and are listed here with permission. These are among the benefits of intergenerational connections:

For children and youth:

- Social skills. Kids learn to talk and empathize with people they wouldn’t otherwise meet.

- Emotional support. Older adults shepherd kids through difficult times and situations.

- School performance. Attendance, behavior, and performance improve. Struggling readers, for example, have made significant gains after being paired with elder tutors.

- Safe and healthy choices. Older adults divert kids from trouble and steer them toward success.1

For older adults:

- Isolation and loneliness. Older adults who were previously cut off from their communities find connection and companionship.

- Mood and self-esteem. As they help kids, older adults are reminded of their competence and achieve a renewed sense of purpose.

- Skills and knowledge. Kids introduce older adults to new technology and cultural phenomena.

- Exercise. To keep up with kids, older adults need to keep moving, which, in turn, boosts their cognitive, mental, and physical health.

- Practical assistance. Young people help older adults with chores and errands.

- Perceptions of young people. Older adults feel more comfortable around kids and more invested in their well-being.

Demographic Reality

So why should intergenerational connectivity matter to local government managers, and why now?

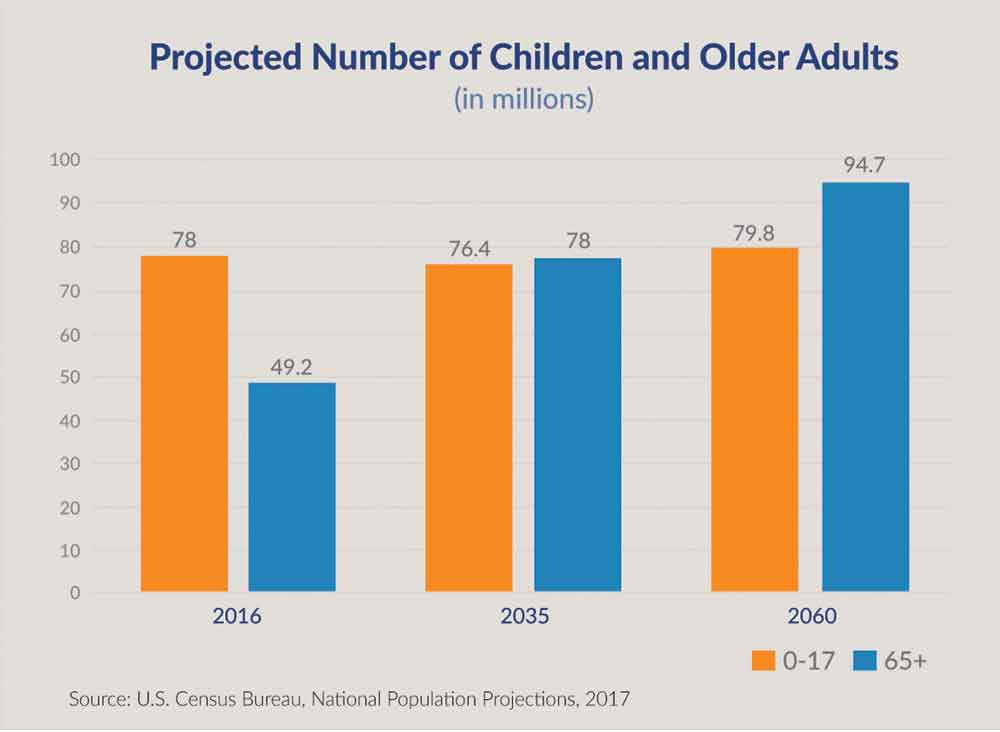

Children and youth and older adults comprise a significant and collectively growing portion of the U.S. population. Children, age 17 and younger, and older adults, age 65 and above, included 122.8 million people or 38 percent of the population in 2016, according to census estimates.

By 2035, their numbers are projected to rise to 154.4 million; and by 2060, to 174.5 million or 43.3 percent of the population.

While some youth and older adults are wage-earners, including those who delay retirement, the percentage of the rest of the population—those in their primary earning years—declines from 62 percent in 2016 to 56.7 percent in 2060.

In sheer numbers, the young and the old, including those more likely to be dependent and/or require ongoing care, are projected to rise by an astonishing 50+ million between 2016 and 2060.

The situation is more acute in Japan, where the aging of the population, a low birth rate, and relatively low immigration are expected to overwhelm the country’s social security system and availability of caregivers for older adults.

Part of the solution in that country is to increase intergenerational connections through programs and activites where young and old get to know one another, so that more young people are willing and able to help care for older family members and neighbors. Increasing immigration is also being discussed.

Fostering connections between young and old and those who care for them is fast becoming a social and economic necessity in Japan and the same is increasingly true for the U.S.

Now is the time for communities to prepare for the looming reality that older adults, children, and youth will represent a growing percentage of the people living in the U.S., not those in their peak-earning and tax-paying years. It is either a looming crisis or an opportunity to redefine how we shape the future.

All social and economic groups within the population can benefit from approaching the future development and well-being of an area through an intergenerational lens. That said, the need for public sector attention will be greater in some parts of a given area than in others—areas with fewer economic resources and where residents have fewer opportunities in life.

Focused intergenerational investment and attention in these areas, integrated with other community revitalization efforts, could help reduce social ills and improve the well-being of all.

Mobilizing Communities

There are “age-friendly communities” or “communities for all ages” in many places across the U.S. Some of them cite intergenerational activities with and for youth but are chiefly about the need for more options and opportunities for older adults.2

And while there are coalitions for children and youth in many communities, there is no all-hands-on-deck counterpart of the all-ages and age-friendly movement for children and youth that has achieved the kind of near-critical mass that these communities have. Note: UNICEF has launched a Youth-Friendly Communities Initiative, but it is young and has not taken hold in the U.S. in a significant way at this writing.

On the intergenerational community building front, Matthew Kaplan of Penn State University, Mildred Warner of Cornell University, Nancy Henkin, formerly of Temple University, now of Generations United, and others write extensively and compellingly on the subject. For more information on their work, refer to this article’s resources list.

Communities for All Ages mobilizations is an approach to intergenerational community building developed by Nancy Henkin while head of the Intergenerational Center at Temple University. It is an approach that Generations United and Dr. Henkin continue to promote.

Here are elements that either occur alone, in groupings, or as a total community strategy in communities aspiring to be intergenerational:

Intergenerational shared sites. Settings that house programs and activities for older adults and for children and youth with planned and informal interaction between the two. This concept goes beyond children trooping through older adult housing at holiday time and instead embraces, for example, a child care center housed in an independent living complex in which older adults and children interact regularly.

Attention to grandfamilies. Programs, services, and advocacy intended to help grandparents (and other relatives) with the challenges of raising grandchildren, one of the key issues being that relative caregivers seldom access the same benefits and supports as unrelated foster parents.

Intergenerational housing. Bridge Meadows in Portland, Oregon, is a flagship for this fledgling movement. The concept is housing that is inclusive of older adults and households with children, including grandfamilies and those headed by older adults, with accessibility for all (i.e., universal design), and design that encourages interaction between young and old.

Intergenerational community events. Community convenings or rallies to educate and excite people about the value and practices of intergenerational action, for example a “future fair” demonstrating intergenerational programs and activities that young and old can enjoy together.

Intergenerational community building. Structured mobilization of young and old for young and old and the community, typically starting with a community assessment and leading to a plan of action and implementation of action strategies.

Intergenerational planning. Generations United and the American Planning Association are developing this concept, responsive to the demographic imperative this article cites.

The kind of planning envisioned seeks to weave population cohorts, particularly young and old and connections among them, into planning by local authorities, potentially leading to an enhanced standard of practice for community planning going forward.

Viewing communities through an intergenerational lens is not an option; it is a necessity and not in some far-off future, but right now. Beyond employing a lens is action, specific to each community, and that requires planning.

City and county managers are ideally suited to be adopters of approaching community as an intergenerational entity, where connecting generations leverages the best we can achieve for people and the communities where they live.

SIDEBAR: How to Unite Young and Old in Big Cities: Lessons from San Diego County

No American metropolitan area has done more to unite the generations than San Diego County, where the local government considers age integration a core community value.

The county employs five “intergenerational coordinators”: one in the department of aging services, one in the department of child welfare, and one in each of three geographical regions. The coordinators work together, with their colleagues throughout county government, and with leaders in the nonprofit and business sectors to create opportunities for the young and the old to serve one another and the broader community.

The county library department, for example, recently asked the coordinators for help designing intergenerational programs at its branches, and the county parks department wants guidance on uniting the patrons of one of its teen centers with the elder patrons of a nearby community center. The coordinators are helping both departments create surveys to assess what sort of programs might succeed; later, they’ll help launch, advertise, and implement the programs.

The coordinators also oversee two “intergenerational councils,” one in the northern part of the county and one in the eastern, that give officials from the public and private sectors a chance to strategize together. The councils meet every other month.

Source: I Need You, You Need Me: The Young, the Old, and What We Can Achieve Together, a 2017 background paper published by Generations United (www.gu.org) and The Eisner Foundation (www.eisnerfoundation.org). This paper is available at http://www.gu.org/RESOURCES/PublicationLibrary/INeedYouYouNeedMe.aspx.

Irv Katz is a senior fellow, Generations United, Washington, D.C. (ikatz@gu.org; www.gu.org).

- https://legacyproject.org/guides/intergenbenefits.html.

- More information on local community efforts can be found at https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/network-age-friendly-communities/info-2014/an-introduction.html and https://www.aecf.org/resources/communities-for-all-ages-planning-across-generations.

American Planning Association (R.A. Ghazaleh, Esther Greenhouse, George Homsy, Mildred Warner), Using Smart Growth and Universal Design to Link the Needs of Children and the Aging Population, https://www.planning.org/publications/document/9148235.

- Brown, Corita; Henkin, Nancy, Building Communities for All Ages: Lessons Learned from an Intergenerational Community-building Initiative, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/casp.2172.

- Brown, Corita; Henkin, Nancy, Communities for All Ages. Intergenerational Community Building: Resource Guide, (Journal of Intergenerational Relationships), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15350770.2015.1058317?journalCode=wjir20.

- Generations United, The Eisner Foundation, I Need You, You Need Me: The Young, The Old, and What We Can Achieve Together, https://www.gu.org/resources/i-need-you-you-need-me-the-young-the-old-and-what-we-can-achieve-together.

- Generations United, MetLife Foundation, Creating an Age-Advantaged Community: A Toolkit for Building Intergenerational Communities that Recognize, Engage and Support All Ages, https://www.gu.org/resources/creating-an-age-advantaged-community.

- Generations United, MetLife Foundation, Best Intergenerational Communities Awards, https://www.gu.org/what-we-do/programs/best-intergenerational-communities-awards.

- Kaplan, Matthew; Sanchez, Mariano; Hoffman, Jaco, Intergenerational Pathways to a Sustainable Society, https://www.springer.com/us/book/9783319470177.

- Warner, M.E. (2017), “Multigenerational Planning: Theory and Practice,” http://cms.mildredwarner.org/p/282.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!