Read Part 1 here.

It was the night before Thanksgiving, and I (Heidi Voorhees) was at the local grocery store with my 18-month-old son and my 5-year-old daughter, buying ingredients for our contribution to the Thanksgiving festivities. At the checkout, I was carrying my son, who was determined to get the candy located nearby. The woman ahead of me in line looked at me sympathetically, and then just as my son put his hands on my face, she asked me if I knew when her street would be resurfaced. Speaking through my son’s fingers, I asked as professionally as possible, given the circumstances, if she could call me on Monday, and I could give her the information.

I lived where I worked for 14 years, with 10 of those years serving as the village manager. Residency had its advantages and disadvantages with respect to the ability to maintain a healthy work-life balance.

In our November PM magazine article, “Living Where You Lead,” we examined the results and effects of residency on the recruitment and retention of managers and administrators based on a survey completed by 446 managers and administrators nationwide. In this article, we will delve deeper into the survey results related to how residency impacts work/life balance and share coping strategies for maintaining a healthy balance, no matter where you live and work.

Survey Findings on Work-life Balance

This article begins with an examination of those who responded to the survey on whether they felt they maintained a sufficient work-life balance. The overall results show that 4% indicate a “very poor” balance, 20% indicate a “poor” balance, 19% indicate having “neither a poor nor good” balance, 43% indicate a “good” balance, and 14% indicate having a “very good” work-life balance.

We then examined the data based on the type and size of the community a manager worked for, regardless of whether they lived in the community or not, to gain a better understanding of how well one feels about maintaining a sufficient work-life balance:

- In suburban communities, respondents noted a more favorable work-life balance than their counterparts in rural or urban communities. Those reporting a “very poor” to “poor” work-life balance were 19% suburban managers, 34% rural managers, and 29% for urban managers.

- In communities less than 5,000 in population and more than 100,000 in population, managers report a higher rate of “very poor” to “poor” work/life balance than the municipalities of other sizes.

Managers in smaller communities typically perform a wide variety of functions for their community, which often puts them in more regular contact with residents. Managers in larger cities also report poorer work-life balance than their suburban counterparts. This may be due to more media/social media attention on their positions.

We then parsed the data to specifically examine the type of community and how those who are required to live in the community compared to those who voluntarily chose to reside within their community feel about their work-life balance.

This set of findings reveals that 34% of the respondents who are required to reside in the community where they work report a “very poor” to “poor” work/life balance. Interestingly, this number drops to 20% of managers reporting a “very poor” to “poor” work/life balance when they live in the community but are not required to do so. They chose residency as opposed to having it imposed upon them.

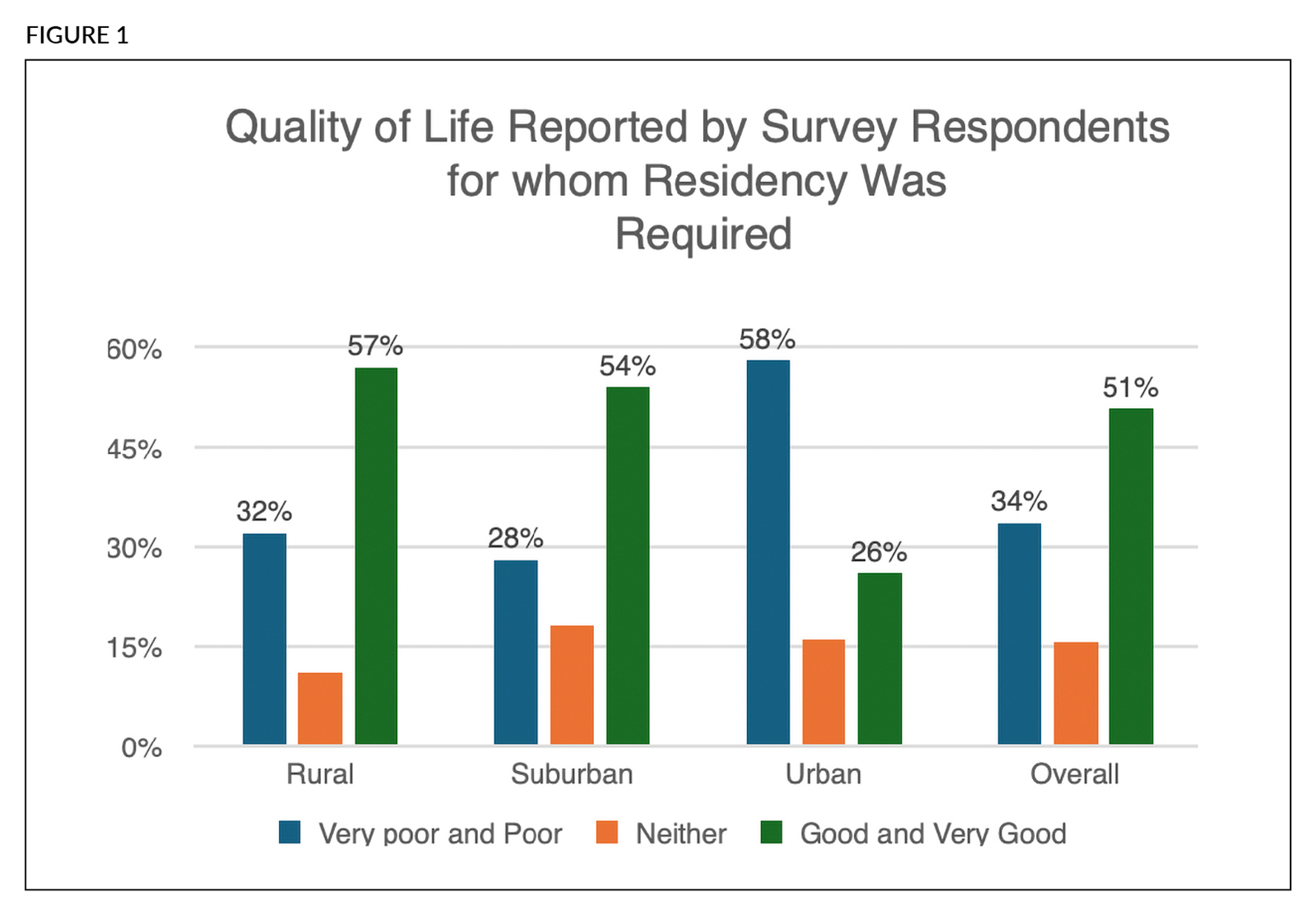

The data also reveals that the percentage of urban managers who are required to have residency in the community has the highest percentage of “very poor” and “poor” work-life balance compared to their rural and suburban counterparts. (See Figure 1.)

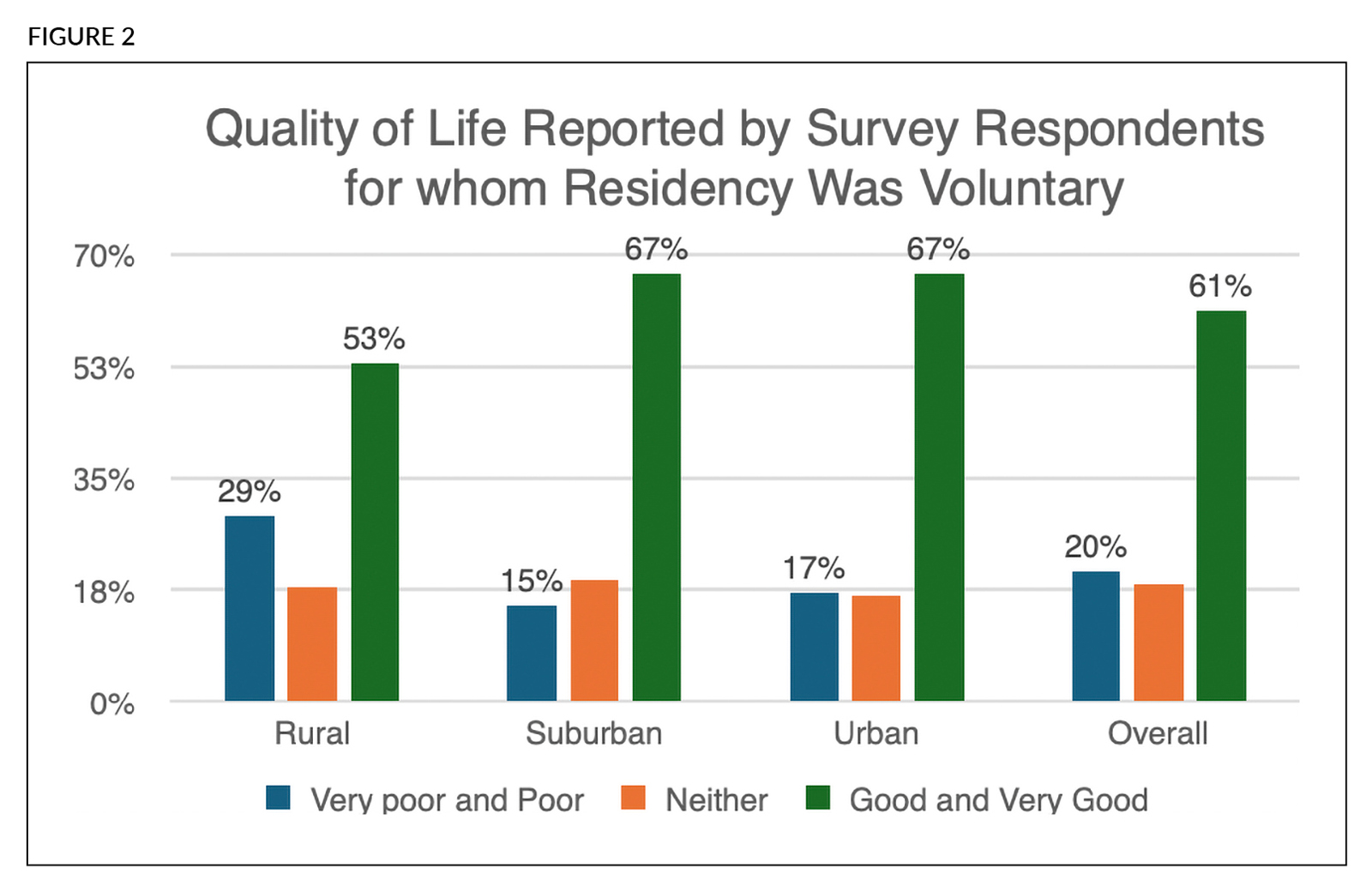

On the other hand, the percentage of rural managers who voluntarily live in their communities has the highest percentage of “very poor” and “poor” work/life balance. (See Figure 2.)

Overall, 51% of managers who are required to live in the community where they work reported having a “good” and “very good” work-life balance. This number increases to 61% of respondents who live where they work but are not required to do so. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

It makes sense that control over where one lives and how one lives might impact feelings of work-life balance. Years ago, a psychology researcher named Angus Campbell found that happiness in life is tied to control. Campbell said, “Having a strong sense of controlling one’s life is a more dependable predictor of positive feelings of well-being than any of the objective conditions of life we have considered.” When residency is required, managers often find themselves choosing a smaller or otherwise less desirable home to live in to afford their new community, or they make compromises regarding their partner’s career or children’s school. Managers are often at the peak of their career when their children are in middle school or high school, making a forced move for career advancement very personally challenging. Elected bodies would be wise to consider this concession if they are interested in the retention of their new manager.

Survey Findings on Contact with Residents and Community Stakeholders

One of the survey questions focused on manager contact with residents and other community stakeholders outside of normal working hours. The data was broken down by managers

who lived in the community where they worked versus those who did not live in the community where they worked. Forty-six percent of managers who live in the community where they work reported “very frequent” to “somewhat frequent” contact, while 29% of managers who do not live in the community where they work reported “very frequent” to “somewhat frequent contact.” Those managers who shared their thoughts on the topic cited several advantages to living in the community where one works, frequently mentioning the following:

• Many managers noted that living in the community enables them to be more accessible to the community. They noted that having more frequent informal interactions with neighbors and other residents during off hours can improve relationships between local government and the community.

• Having greater access and interactions with residents and community stakeholders enables managers to position themselves to anticipate, gain a greater understanding, and be more responsive when an issue or problem arises.

• Gaining the perspective of a resident helps inform their work in formulating policy.

• Residency promotes credibility with their elected officials and residents within their community.

• Residency can help managers gain a better pulse on what is going on in the community.

Residency Advantages for Work-Life Balance and Impact on Family Members

From the survey, those managers who reside where they work cited the following advantages:

• Living close to home: According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the average commuting time in the United States is 26 minutes each way—nearly an hour a day. Reducing this substantially can provide a few more hours for activities more enjoyable than commuting.

• Proximity to children’s schools: The ability to volunteer easily or attend school events (using personal time, of course) or be available for emergency calls was noted.

Non-Residency Advantages for Work/Life Balance and Impact on Family Members

From the survey, those managers who do not live where they work cited the following advantages:

• Anonymity: Managers can maintain a certain level of anonymity. One manager stated they can run errands on the weekend in their gym clothes without worrying about running into residents.

• Impact on family: Many managers commented that not living in the community they serve is important for their family. Their spouse and children are not questioned about the decisions that the manager makes, nor subject to any backlash from those decisions.

• Spouse’s career: Relocation can be difficult in two-career households. Managers in a suburban environment can often change positions without relocation, thus not impacting their spouse’s career.

• Children’s schools: Relocation can also be challenging when the manager has school-age children. Managers are hesitant to relocate, particularly when their children are in high school. Parents of a child with special needs also hesitate to relocate at any time if their child is doing well in their current environment.

• Friendships without hidden agendas: Managers who live outside of the community can develop friendships and social connections without fear of accusations of favoritism or concern that there is an ulterior motive for developing a friendship with the manager.

Managers who do not live in the community where they work were universal in noting the need to attend festivals and community events; eat in local restaurants; volunteer in the community (Rotary, Lions, or other service organization); and generally be visible and accessible to the residents and other stakeholders. Many highly successful managers have followed this path and have been so visible that many in their community thought they lived there.

Strategies for Improving Work-Life Balance

The survey comments show that managers understand they are public figures and subject to contact outside of working hours, but as one respondent said, “At times it can be overwhelming.” Respondents to the survey cited the following strategies for improving work-life balance when living in the community:

• As previously mentioned, many managers noted the importance of shopping locally, volunteering, and attending festivals and community activities. They went on to suggest, however, that it was important to belong to religious institutions outside of the community. This can be particularly important if the manager’s religious involvement includes “being vulnerable,” as one respondent commented. One former library director noted that many years ago he had to change his church attendance to one outside of the community where he lived and worked. He did so because the church members brought books to church services, so he could return the books to the library.

• Similarly, several managers agreed with engaging locally through community activities, volunteering, and shopping, but also the need to go outside of the community for recreational and entertainment activities, ensuring quality time with their family.

• Another suggestion is to manage finances, haircare, and healthcare outside of the community to ensure privacy.

• While some managers said they do not take any extra steps to ensure their privacy, others commented on setting boundaries with residents who approach them on the weekend with non-emergency issues, saying they would “be happy to speak with them during working hours or to set up a time that is convenient for both parties.”

• Many respondents said they have very minimal or no personal social media to preserve their privacy.

• One respondent said they grocery shop “entirely on Instacart, knowing that a trip to the grocery store is a community meeting.”

Many of these suggestions work more effectively for managers in a suburban environment where options for healthcare, entertainment, shopping, religious observance, and recreation outside of their community are more available. This is likely the reason more suburban managers report a better work-life balance than their rural or urban counterparts.

Finally, ICMA has published several articles and developed a number of resources on strategies for maintaining a healthy work-life balance, including an entire issue of PM Magazine, titled “Making Work-Life Balance a Priority.” Additionally, an ICMA senior advisor in your state can serve as a trusted and confidential resource for you if you are seeking additional support.

Concluding Comments

The advantages and disadvantages of residency will continue to be discussed and debated by local government leaders. While everyone in the local government profession understands they are “living in a fishbowl,” each person likely has a different tolerance level for how transparent the fishbowl walls are. Some may be completely comfortable with total visibility, while others want the walls to be more opaque, while still others may want to duck behind a large rock or tall grass in the fishbowl from time to time. Community visibility is often a family decision as well. While the manager may be completely comfortable with their high-profile career, their family members may not be as comfortable.

As local government professionals evaluate the next step in their career, they must thoroughly consider the many sides of residency and non-residency in the community they serve and how it fits with their own and possibly their families’ tolerance for visibility.

HEIDI VOORHEES is a former village manager and consultant and is now retired. She serves as a volunteer coach through the ICMA Coach Connect program and continues to write and speak on issues pertaining to local government.

MITCHELL BERG, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor at Indiana University’s Paul H. O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs.

IAN JAMES is a recent graduate of the IU Paul H. O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs program and is currently completing an internship in the town management office of Plainfield, Indiana.

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!